A Glimpse at the Past

What We Once Learned: A look at an old Social Studies textbook

It's no secret that I love old social studies books - I have a collection of about ten now, and it's always kind of fascinating to delve into them. Doing so isn't just a matter of curiosity on my part of course. It also helps me see just what kinds of things were being taught and promoted at a given time. Having that historical context is always pretty interesting. So out of curiosity I decided to take out one of these tomes and explore its demographics. Basically I wanted to know not only how history is presented by this textbook but who the historical actors included are. With that in mind, let's get started.

The Book

For the purposes of this exploration I used Exploring American History, a secondary textbook published in 1938. Its principle authors were Mabel B. Casner of the Washington School in New Haven, Connecticut and history Professor Ralph H. Gabriel of Yale Univeristy. It also cites an advisory board consisting of J. Russel Smith (professor of economic geography, Columbia University), Willaim G. Kimmel (former supervisor of social studies in New York state) and R.V. Harman (school of education faculty, University of Missouri). Interestingly the maps were drawn by George Bell, who'd worked on popular publications such as Time and Fortune. The book's chapters are referred to as 'problems' and organized into chronological units; each problem has a set of discussion questions at the beginning and activities at the end. By stamps in the book it was used by Douglas High School in Dillard, Oregon.

What We're Looking For

Now that I've introduced the book itself, what kind of information are we interested in finding? I was curious about what ethnic groups were represented in Exploring American History, so I generated a list of potential ethnicities the text might touch on. These included: white Europeans, Native Americans, African Americans, Hispanics and people of Asian or Middle Eastern descent. Armed with this list I realized it might also be important to see not only who was discussed, but how they were discussed. This led me to decide how I would demonstrate the demographics of the text.

Analyzing the Data

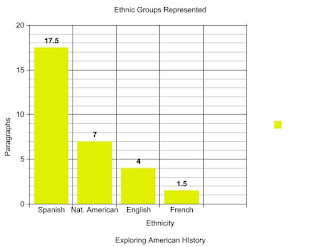

Knowing what I'm looking for, I decided to add ways to measure the data I collected. To measure the weight given to each ethnic group represented I would record how many paragraphs were devoted to each. Since the text's chapters are organized into sub-headings of between one to six paragraphs this seemed the most efficient way to gauge the demographics. In order to get a picture of the text's tone, I would also keep track of how the group in question was presented - either in a positive, neutral or negative light - and how many paragraphs were dedicated to a given tone. Armed with this, I dove into Exploring American History.

What I Found

To make things easier, I decided not to look at the entire book (which is over 600 pages long!). Instead I focused on two chapters, or 'problems' in the text's vernacular. Specifically chapters on periods which I knew could be contentious, dealt with multiple ethnic groups and thus might contain important omissions. For the purposes of my investigation I chose chapters on the European conquest of the Americas ("What were the results of Spain's discovery of gold in America?") and the roots of the American Civil War ("Why did the United States divide into two warring sections?"). First up, European colonialism:

As can be seen here, Europeans made up the vast majority of page space in this chapter. Spain is represented the most, having twice as many paragraphs discussing them than any other ethnicity. While England and France are part of the text's story it mainly focuses on the actions of Spaniards during this period. Native Americans are represented by a good number of paragraphs but combine different nations including the Aztec, Inca, Pueblo and Cherokee.

Being the main focus of the chapter, Spaniards are treated mostly as heroic, bold adventurers who were after glory and fame. I was pretty surprised to find that some atrocities committed by the Spanish were at least referenced in the text, however. For instance it mentions how de Soto enslaved natives and forced them to wear chains, natives were forced to work in Spanish mines and fields and that the Spanish lords acted cruelly. It also takes time to criticize the Spanish society in its colonies, citing severe economic inequality and disregard for their subjects. It's important to note, however, that Spanish missionaries are portrayed in an entirely positive light along with the King. They are portrayed as wanting the natives to be happy and to see the light of Christianity.

Native Americans play a major role in the chapter but their treatment by the authors is largely evident of tokenism. They are portrayed as being noble but misguided people who were apt to lash out violently at perceived weakness in their own culture and destroy the buildings and belongings of Christians. Often they are described as becoming good friends with missionaries, happier after conversion and enjoying life on Spanish mission lands. When they are actually depicted positively, the text mentions how Native traders established trade routes all the way to Florida from Mexico and that they were proud people who fought bravely.

Despite the extent to which French colonialism took place in America, they are barely mentioned in the chapter. When they are it is as antagonists to the Spanish who are trying to establish their own colonies. No real moral judgment is used for them, they simply exist.

Of any of the European ethnic groups discussed in this chapter, the English get the most overtly biased treatment. None of the material is anything but glowingly positive. When they first appear the English are praised as being strong and brave, led by a wise queen and weirdly praising Shakespeare in the same paragraph. English culture is presented as superior to any other in the chapter. A section on English piracy praises the 'Sea Dogs' who helped defeat the Spanish, and the Spanish Armada's defeat is celebrated as well.

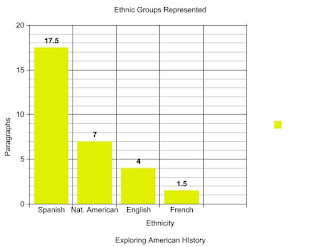

Before offering a final analysis, let's have a look at the chapter on the roots of the American Civil War. For this chapter I established that there were three major groups being discussed - White Americans, African Americans and Mexicans. That said, here is my data:

With the topic being entirely about American history without those pesky Europeans around, the main focus becomes white/European Americans. The vast majority of topics are entirely from the perspective of this group, particularly white men. Both North and South are included in this but there is very little room for other groups to even appear. African-Americans appear only when the topic of slavery is discussed and even then usually in passing. More on that in a moment. Part of the roots of the conflict deal with Texas and the war with Mexico, so Mexicans are given a little bit of space as well.

As mentioned African-Americans are only discussed when slavery itself is, and then mainly in passing. The bulk of their contribution in this chapter is the Dred Scott case. Even that is not really about African-Americans at all, but rather the ruling handed down by the white Judge Taney! The negative perspective comes into play early in portraying slaves as happy to serve on a young Jefferson Davis' plantation. As far as this text is concerned African-Americans are nothing more than set pieces for a stage dominated by white men.

Clearly showing a bias for the European descended Americans, the only mentions of Mexicans in the chapter deal with Texas and their war with the United States. All that is said about them is negative: they didn't know how democracy worked, mistreated American settlers and their whole government was inferior to the Articles of Confederation. Thus the text justifies America's annexation of Texas and the southwest.

The main ethnic group discussed in this chapter was Americans of European descent, and was overly positive in most accounts. It reminds me of what Loewen describes as the American Legion influence on social studies texts - that it must be 'optimistic'. Men from both sides of the Civil War are treated as heroic. Southern senator Calhoun's speech on Southern grievances regarding slave vs. free states is given nearly a full page on its own, while Lincoln has two speeches quoted in part. Yet despite the optimistic and passive tones the text takes most of the time, it makes clear that slavery was a central issue in causing the Civil War. While at times the South is romanticized the text carries a Northern bias that reminds the reader that slavery was a major motivation.

Conclusion

What we see in this 1938 textbook is a clear preference for European and white American perspectives on history. Non-white ethnic groups are barely given the time of day, and when they do appear they are presented as inferior to the Europeans. There's no diversity in the perspectives at all, even when it comes to the Europeans. The authors are promoting Anglo-American superiority in military and civil matters, along with Christianity as the only true guiding compass of morality. What is odd is the occasional mentions of less flattering information - Spanish cruelties to natives and the South's focus on slavery for instance. These can be explained as the perspective of northern, white authors.

What do you think? How does this data reflect on the American educational environment in social studies during the 1930s? What does this tell us about America in general? Please feel free to comment and share your thoughts!